Project update 31 of 76

PCB Redesign and Firmware Progress

Hey there! It’s February, and we have a new UHK update for you. A lot has been happening, and, barring unforeseen delays, we’re on track for April keyboard delivery. Let’s delve into the gory details!

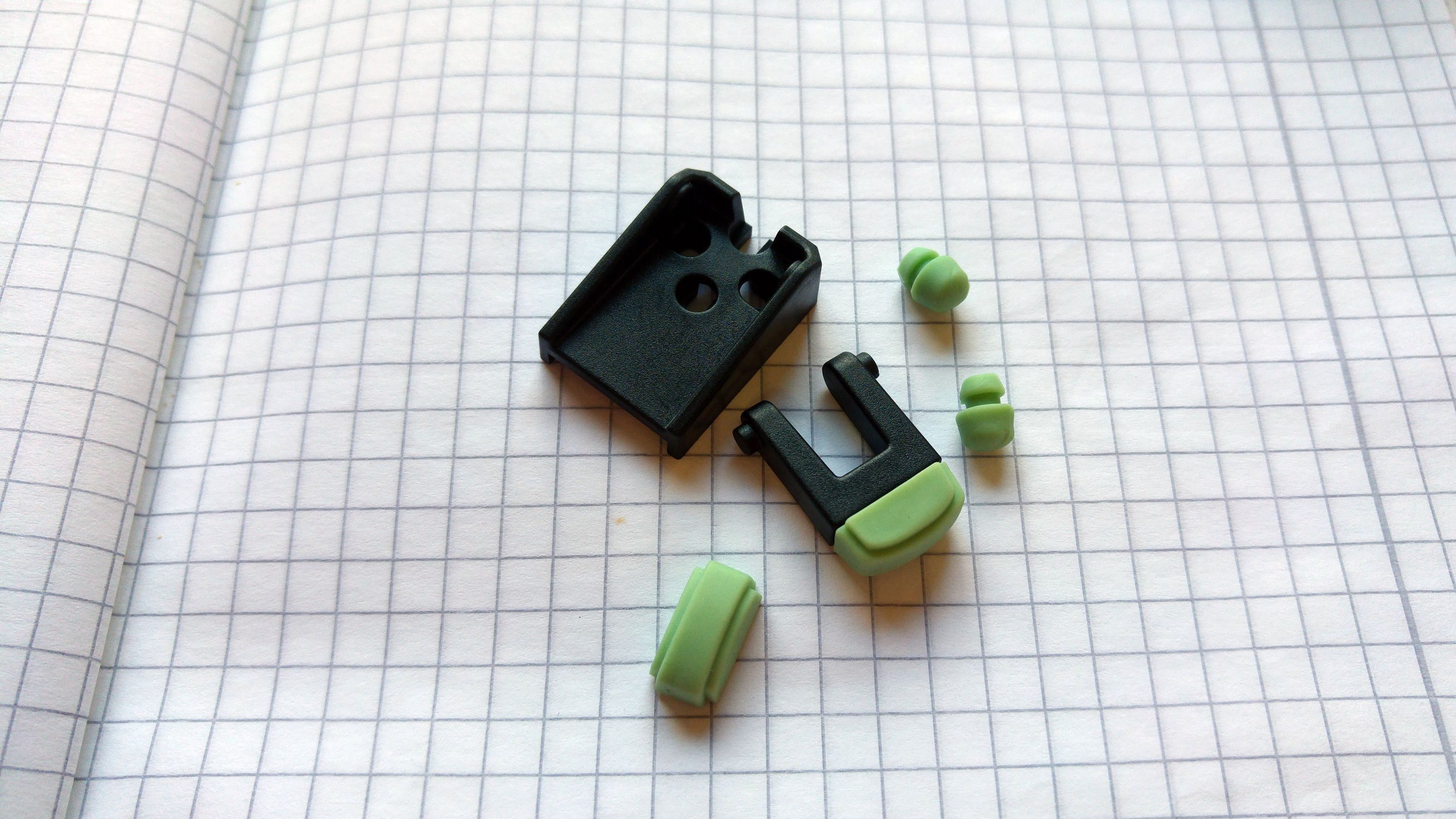

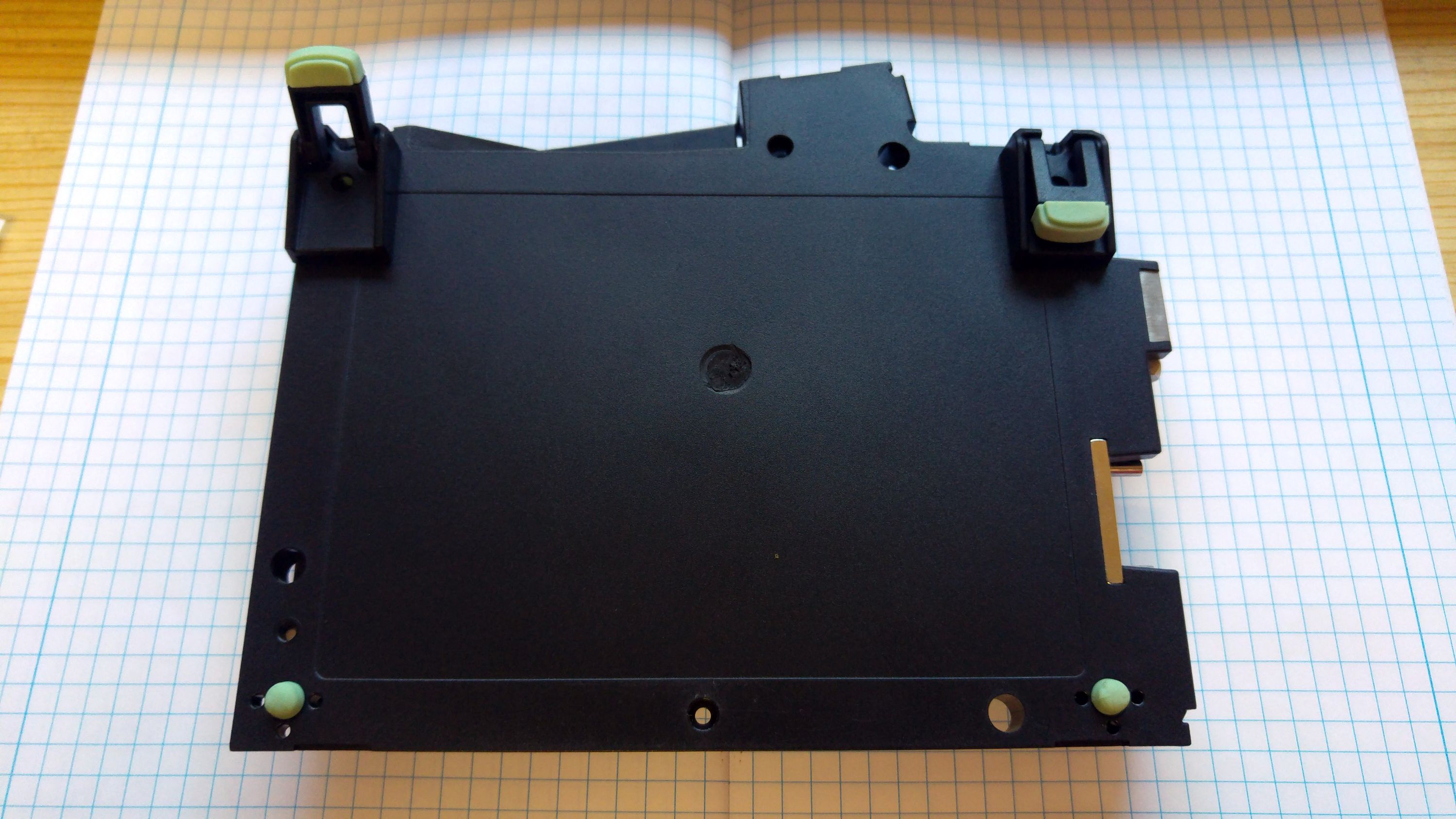

Rubber feet and caps

There are small rubber feet and rubber caps on the ends of the flip-out feet of the UHK. Up until this point, we only had 3D printed versions of these caps, but the tooling has finally been created for them, so we got a couple samples.

The samples are surprisingly good for a first run. There’s only a very slight modification to be done to the tool to make it fit perfectly, which will completely eliminate the parting lines that are now slightly visible.

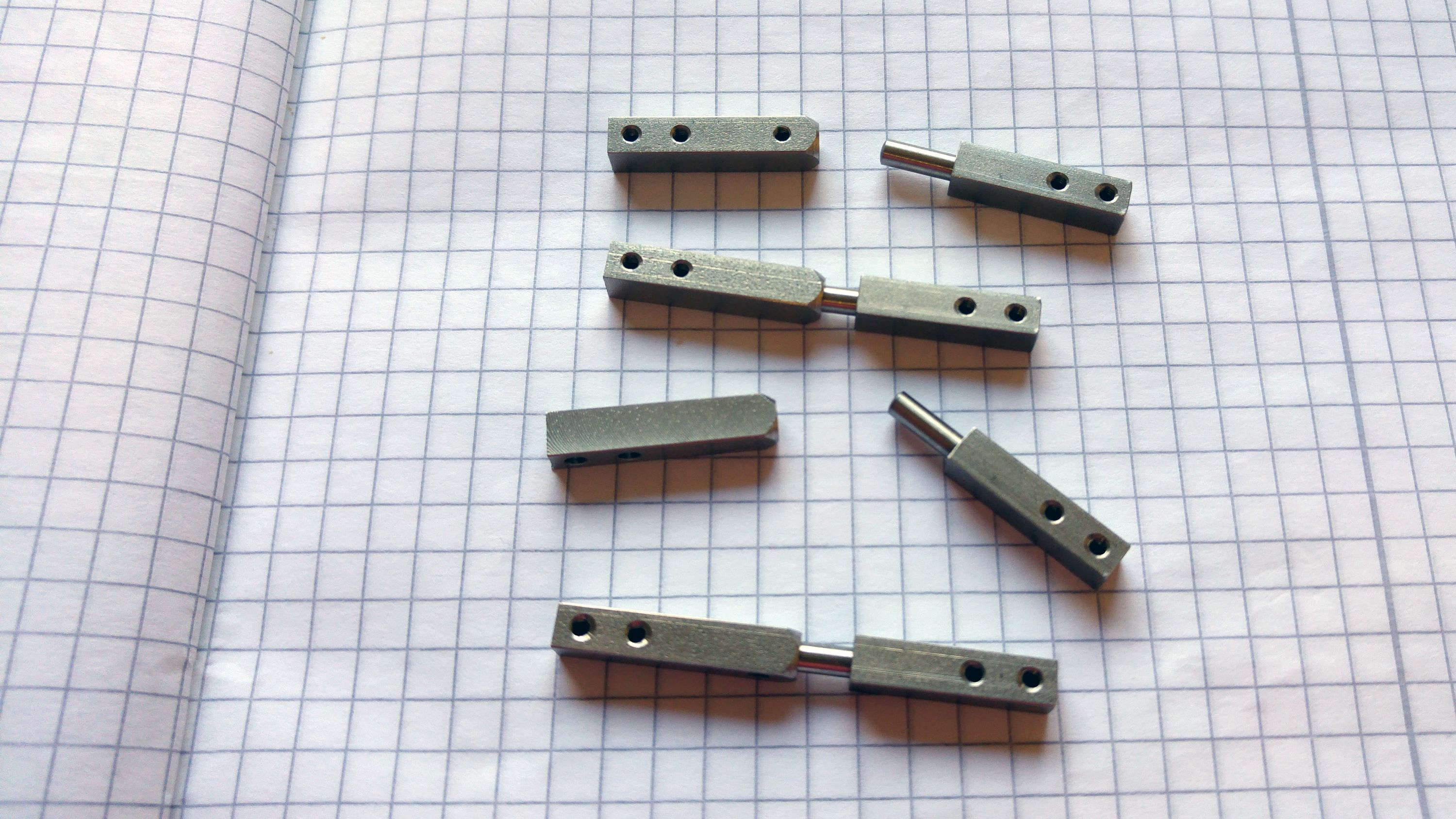

Steel guides

The steel guides are currently being manufactured. Here are some samples before vibration grinding them.

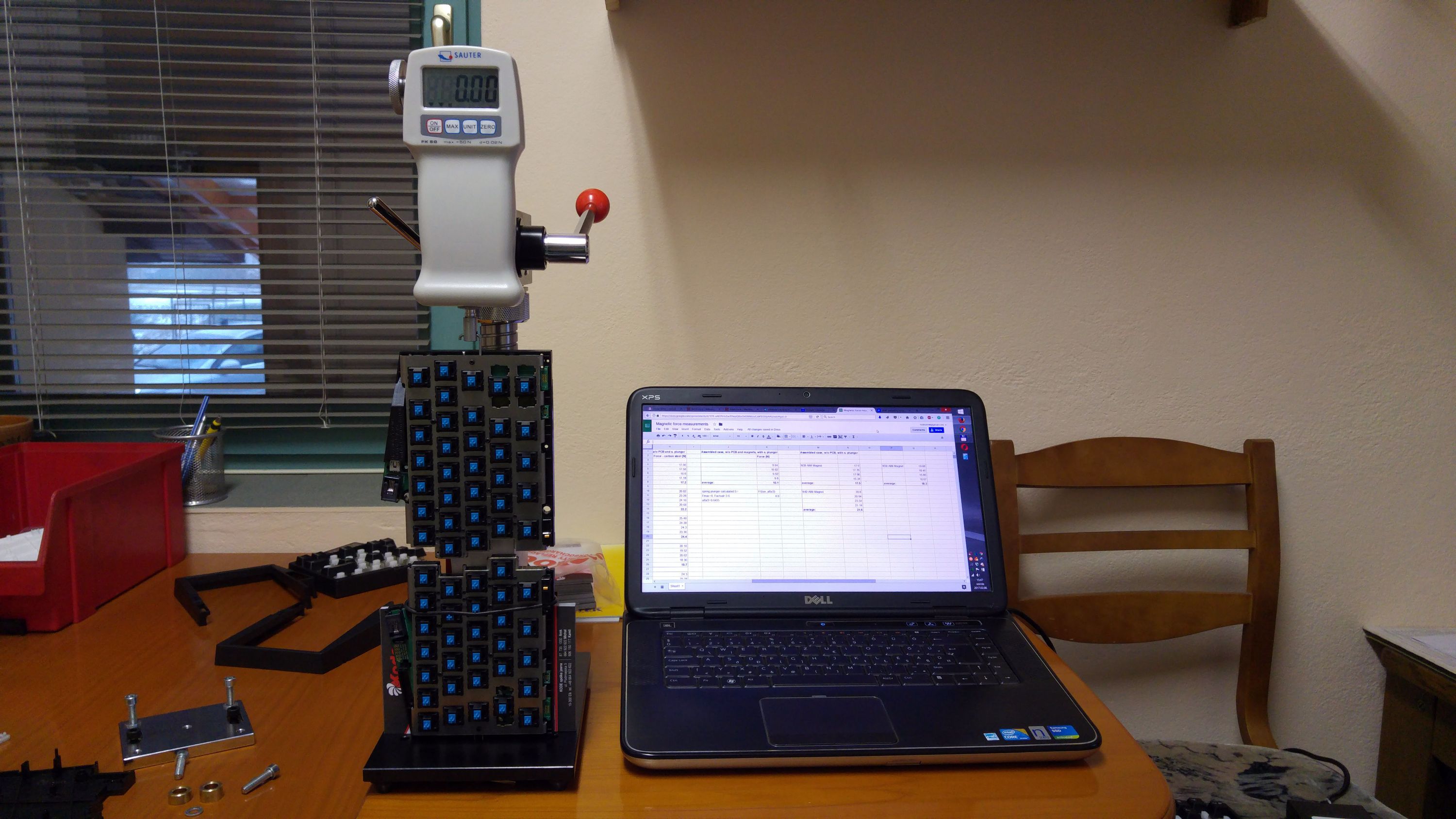

Force measurements

András has made a number of measurements with our new force measurement gauge.

To find the optimal pull force between the keyboard halves, András has made measurements using various magnets. They must not be too strong, but strong enough to prevent the accidental separation of the halves while carrying or during a fall. Some final tests still have to be made in the coming days, then the chosen magnets will be ordered.

Right-half bootloader completed

Even though the bootloader for the right keyboard half was already working, it wasn’t secured. That means that if we transferred a firmware image whose memory region overlapped with the bootloader memory region, the bootloader would have been overwritten by the firmware image.

Luckily, Kinetis devices offer hardware level memory region protection for such cases, which Santiago made a good use of. Now, with the memory protection in place, even if the bootloader would want to overwrite itself, it couldn’t.

But this isn’t the only safety measure that KBOOT, the Kinetis bootloader, provides. Let’s say that the firmware transfer gets aborted due to a power outage or for whatever reason. In such a case, the CRC checksum of the firmware doesn’t get updated and when plugging in the UHK the next time, KBOOT detects the CRC mismatch, and instead of jumping to the corrupted firmware, it stays active, waiting for a new, valid firmware transfer.

With the above protections in place, we believe that the right keyboard half is unbrickable via USB. I’m delighted that NXP offers such a comprehensive bootloader. It makes things so much easier and safer.

Santiago will make the bootloader for the left keyboard half work, too, but there’s something else to be done before then.

Firmware progress

The UHK firmware has already been working for quite some time, but some things weren’t exactly rock solid and optimized. This is about to change.

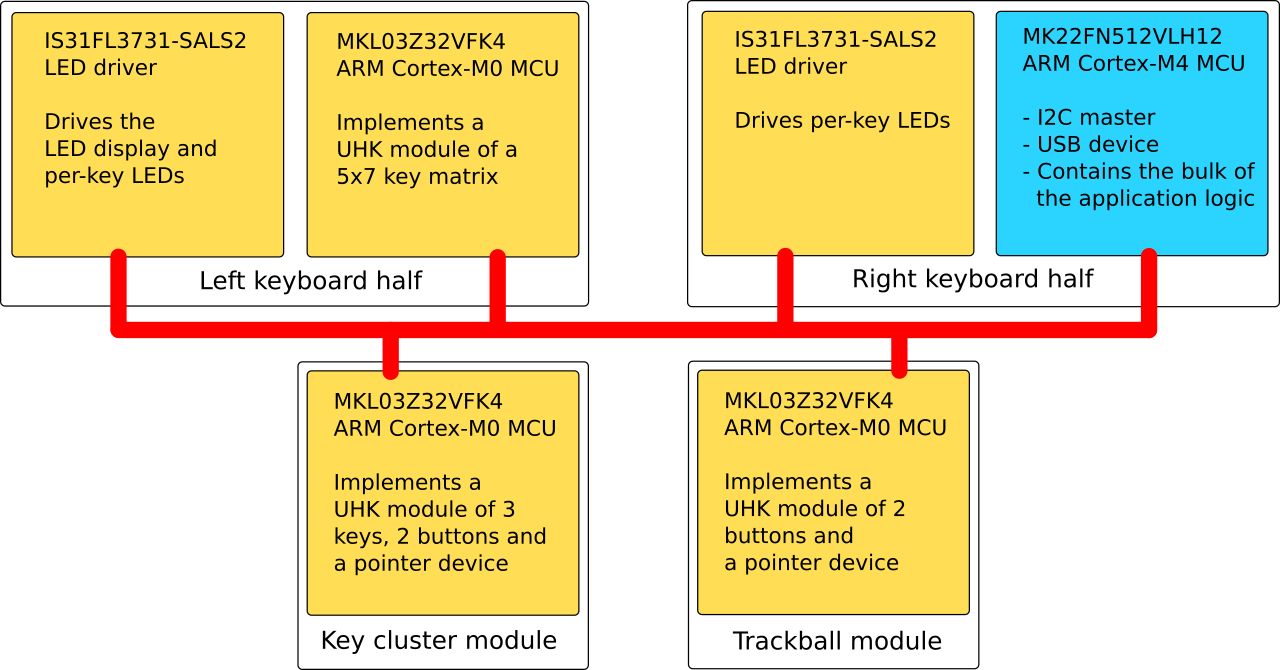

The reliable and resilient communication of the UHK parts is the core concern. If you think of the left and right keyboard halves, and the left and right add-on modules, these are all separate computers, and some of them contain multiple processors. The bus via which they’re interconnected offers a limited (although sufficient) bandwidth which must be utilized as efficiently as possible. To make things even more complex, any module can be disconnected, or connected any time, so hot-plugging must be seamlessly handled.

First up, the communication should be made fully asynchronous. Synchronous communication was easy to implement because it’s just a sequence of instructions, but it’s highly suboptimal because it uses inefficient busy loops instead of interrupt handlers, and it’s hard to do robust error handling with it.

I was aware of these problems from the get-go, but I wasn’t concerned because I wanted to implement a working firmware as quickly as possible and improve it later. Now that we’re marching towards release, it’s time to solve these problems properly.

When changing sync code to async, the application logic changes quite a bit because instead of using a sequence of sync calls, an async callback gets fired whenever a communication event occurs, and a state machine has to be implemented inside of the callback.

I will end up implementing a scheduler state machine, so that the I2C master (the blue rectangle in the diagram above) will talk to I2C slaves (yellow rectangles) in a round-robin fashion. The purpose of these inter-module messages is to propagate state between the modules.

This will result in a very clear programming model in which the scheduler will sync the state of the modules in the background all the time, and the rest of the application logic of the master will be able to deal with the various module-specific data structures as if they were local.

I recently hit a related problem that I was unable to resolve, so in my true style, I summoned Santiago. The problem was that communication did not resume between the halves when I disconnected then reconnected them, even despite using async I2C calls. Santiago looked into the issue and concluded that the KSDK I2C driver is not very robust.

As it turns out, I2C drivers typically assume that I2C devices don’t get hot plugged, but are permanently soldered onto a PCB. Obviously, our situation is different, which calls for a more robust I2C driver on which Santiago is working right now.

PCB redesign

In our previous update, we told you that the UHK prototype has failed the EMC test and that I will find a professional PCB designer who (unlike me) does know what he’s doing.

I’m happy to introduce István Pánti, PCB designer extraordinaire!

István has been using Altium Designer over the years, a commercial PCB designer application which happens to be the number one industry standard worldwide. Luckily, he was willing, and even excited to learn KiCad, and according to his opinion it’s a surprisingly powerful tool for a Free Software package.

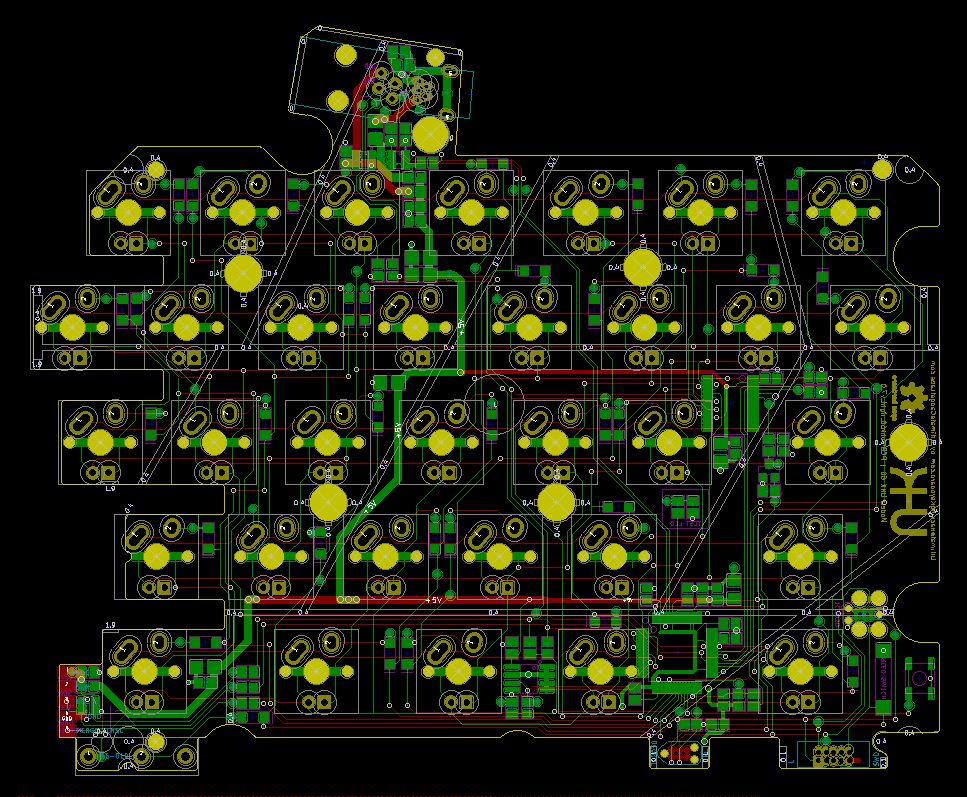

Then he cleaned up all of my traces and most components of the right UHK board, and started to reroute the tracks, beginning with the D+, D- differential pairs of USB, which are supposed to be the most problematic according to the EMC test measurements. His design turned out to be a lot cleaner than mine.

Routing PCBs is not black magic, but it may seem like it to the outsider, especially when dealing with EMC issues. There are a lot of layout rules to follow. Lucky for us, István has routed his fair share of PCBs before, including a USB hub, and read plenty of USB PCB design guidelines which now he puts to good use.

He’s been making great progress recently, and the end of the redesign is near. You can see his progress on GitHub.

I asked him to also create a 4 layer version of the PCBs after he finishes with the 2 layer version. Then we’ll prototype both versions and put them to the test. The 4 layer PCB should perform significantly better in the EMC department, but we’ll only pick it if necessary because it’s also significantly more expensive. This way, we can progress as quickly as possible.

Manufacturing progress

A short overview:

- 2,000 LED displays are being manufactured.

- 16,000 steel guides are being manufactured.

- 4,000 magnet counterparts are being manufactured.

- 2,000 FFC cables are being manufactured.

- We will order 10,000 pogo pins, 126,000 keyswitches, and 126,000 keycaps in a few days.

- 140,000 screws are on their way to us.

Lots of stuff are about to flow in pretty soon. Expect pictures of big boxes filled with goodies!

Thank you for reading the February installment of UHKzine. Talk to you on 2017-03-16!