Project update 2 of 15

RISC-V and the History of POWER

We get asked a lot about why we aren’t using RISC-V for Talos™. This update details our rationale and delves into the long history of POWER over the past several decades.

RISC-V

As you may be aware, instruction set plays a minimal, almost non-existent role in determining the performance of a modern processor design. RISC-V CPUs, while interesting from a licensing perspective, are a far cry from POWER8, x86, or even ARM in terms of raw performance. This is not so much an intrinsic fault of the instruction set as it is a complete lack of any high-performance cores and interconnect that might be able to fully utlilize the attached third-party controllers, such as those for DDR3/DDR4 memory and PCIe 3.0. Furthermore, basic CPU blocks essential to sustained SMP performance and/or basic system security are still absent on RISC-V, such as L3 cache or any type of IOMMU.

RISC-V, which has not even reached production availability for embedded systems as of this writing, is currently only able to compete, at best, against very low end embedded ARM, low-end MIPS, and similar offerings. Worse, by our most optimistic estimates, RISC-V at its current development pace would take well over a decade to approach even the performance of old x86 hardware from the late 2000s (roughly Intel® Core 2 class machines). Finally, there is no real effort being expended to make RISC-V into a workstation or server class processor, and you only have to look as far as current ARM-based SoC offerings to see how difficult and expensive it is to create a credible, high-performance processor that competes in this market space.

POWER8

In comparison, POWER8 is available right now, today, and brings you the best of both worlds. IBM doesn’t want to control your machines; they simply give you very high performance hardware and the tools required to control it, then let you handle the rest — this means your machines can be as secure (or insecure) as you desire. OpenPOWER cores and chip designs can be licensed and custom built by anyone with sufficient resources, providing an unprecendented level of flexibility for design in this high performance class. The continued revenue derived from the manufacture and sale of both CPUs and licensed cores helps to ensure the longetivity and stability of the POWER ecosystem by not only funding future POWER CPU development, but also limiting the ecosystem fragmentation that is currently hindering uptake of ARM and RISC-V.

Evolution of POWER Processors

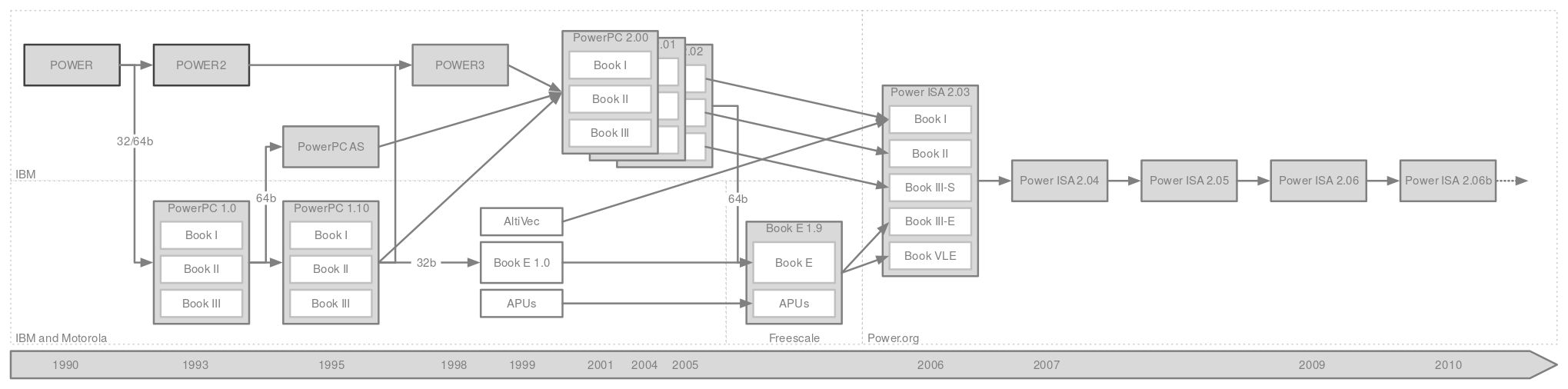

What was required to make POWER8 one of industry’s leading CPUs for raw general purpose compute performance? A lot of well-funded research and very hard work spanning almost 40 years! POWER, which stands for "Performance Optimization With Enhanced RISC", traces its origins back to an ambitious CPU project at IBM in 1977. The goal of this project was to create a high-performance RISC CPU for mid-range workstations and servers. By 1980 the first prototype of the IBM 801 was complete, and further development of the associated RISC concepts led to the first POWER processor in 1990. The newly christened POWER1 along with its successor the POWER2 both found their way into the RS/6000 machines machines of the 1990s.

The POWER ISA has gone though a process over time that should be familiar to almost any open source developer. It was repeatedly forked, merged, and forked again as needed to create processors tailored to specific market segments. One of these forks, technically a fork of POWER1 commissioned by an alliance between Apple, IBM, and Motorola, became the famous PowerPC processor line. Starting with the PPC 601, this lineage was used in Apple products until finally being dropped after using the PPC 970 in the mid 2000s.

The server branch of POWER remained under constant development through the mid 2000s, yielding a continuous sequence of more and more powerful devices. The forks that were not part of this server branch were finally merged back into the renamed, monolithic "POWER Architecture" as of the POWER ISA v.2.04, whose successor was used as the specification for the POWER6 processor. POWER7 was mostly an evolutionary step, while POWER8 is the first OpenPOWER processor and the first POWER processor to officially support true bi-endian behaviour. As such, OpenPOWER CPUs trace their lineage directly back to the very first POWER1 workstation / server CPU prototyped in 1990. Over the years they have gained more CISC operations, vector support, 64-bit support, and a host of other necessary features in much the same way as their x86 competitors, whose history traces a very similar path.

Conclusion

As you can see from this development process, it is quite presumptuous to consider a CPU that has not even reached its first silicon production milestone a worthy contender against the high-end POWER (or even x86) workstation CPUs. POWER was always designed for workstation use, while RISC-V has been designed with completely different goals in mind. If you need a libre core to test a new microarchitecture or core design idea, or are simply targeting an embedded system, RISC-V is a very good choice. However, you’ll be much more efficient creating that embedded design when using an OpenPOWER workstation!